Last winter, I submitted this lil’ bit of flash fiction to a contest. The winner would get a scholarship to attend the 2016 Iceland Writers Retreat. I didn’t win. (But I was a finalist, so that’s something.) I’ve never published the piece—it just languished on my computer and I kept meaning to add to it but never did.

I’ve decided to publish it here. Enjoy!

What the stones know.

Stones are the best storytellers. Few people know this, but that doesn’t make it any less true. Stones, with their ancient hearts and silent breath, speak the beauty of the world more eloquently than any bard, more honestly than any reporter. Even when they’re sleeping, even in the years where they lay dormant, waiting, even now, they still know.

But on the shores of Iceland, some stones still speak. In low rumbles, they reveal their stories. The newer stones, the ones that were forged by fire spit up from the earth (that angry infant still hasn’t cooled at her core), are positively chatty compared to their elder counterparts. And in the center of the country, where stones are split and torn apart, ripped by forces they understand all too well, there the stones speak with rage, telling stories that fall like shards from their mouths, knife-sharp and intended to hurt.

But don’t listen to those stones. Listen to the stones that curl against each other, smooth and round as merry wives. They roll shoulder to shoulder as the waves pull them up and down the shore, and they go with the ocean, happily. These are the stones that tell the best tales.

They tell of fish that are larger than cruise ships, with dull eyes and gleaming scales. They tell of pearl-white seawolves, creatures with large teeth that run through the waves, disguised by the surf and safe in their speed. They tell of men as large as mountains with faces only half as sharp. They tell of cloud women who wrap the air around them in diaphanous cloaks, their feet bare as they step down from the sky and onto the black sand shore, where they gather treasures to bring home to the moon. And sometimes, if you ask nicely, they will tell you of the drowned girl.

She was a child, a black-haired little one who belonged to a fisherman. She lived on a cliff over the sea, near a big stone bridge that attracted tourists with cameras and busses filled with foreign faces. But the little girl ignored them all. She wanted to learn to fly and at night she dreamed of airplanes and engines. One day, as she ran over the stone bridge, arms outstretched like wings, her mouth humming a quiet tune, one foot slipped. It was followed by the other. The bridge had tricked her. The jagged stones had shifted, and so she fell.

The girl was never found, and her father never knew what happened to her. But the stones knew. They curled around her body, one by one, as the waves granted them motion. Salt turned her skin white and the tide washed away the blood. The stones continued their slow crawl over her body, hiding her from sight, protecting her from any more harm. Or perhaps they wanted to keep her on earth, never to fly. Either way, she is gone, and only the stones know where to find her bones.

Related: Image-based fiction, inspired by Finland.

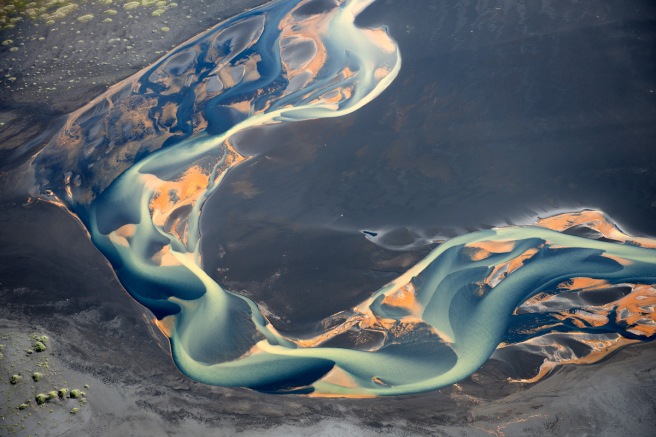

Above image: Detail from a painting by Rebecca Chaperon.